01. Enrollment of the first emigrants to Brazil

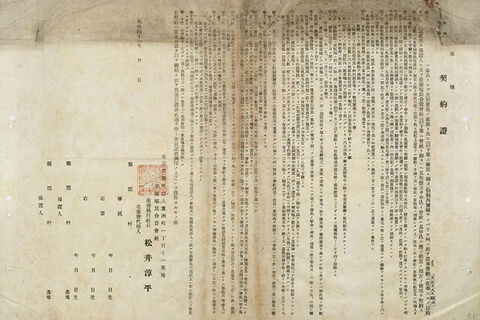

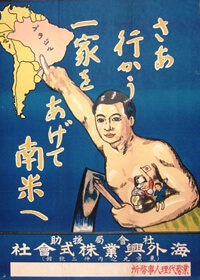

In November 1907, KOKOKU SHOKUMIN KAISHA (Imperial Colonization Company) was a rising emigration company which saw the possibility of emigrating to Brazil, and signed an agreement with the high official of the State of São Paulo to transport 1,000 migrant families per year. The Brazilian side demanded a family immigration expecting for them to set up on the farms for an extended period, not as a temporary job for them to soon return. There was also the condition to arrive in Brazil by May, the season of coffee harvesting.

The Imperial Colonization Company obtained permission from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in February 1908, then started the enrollment process for emigration, but already being impossible to arrive in May, obtained the consent of the State of São Paulo to postpone the arrival to June and instead hastily sought the enrollment of a thousand people.

The search for emigrants focused on Okinawa Prefecture that had experience in subtropical agriculture, a similar climate to São Paulo, as well as the experience of sending emigrants abroad among others.

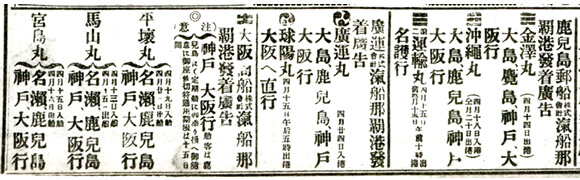

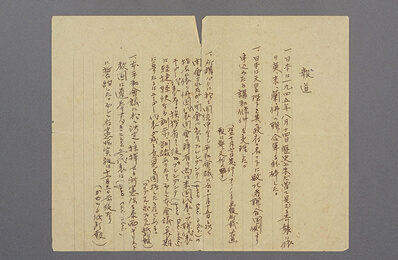

According to a newspaper article, the departure from the Port of Naha was scheduled to be around April 8, but considering the advertisement for the enrollment of emigrants were still published on March 29, we can notice there were less interest than expected.

The Emigration Registration Guide of the Imperial Colonization Company

The content of the enrollment guide said that the trip was an out-of-pocket cost, but it had a couple of extremely favorable conditions. The salary in particular -- "with the daily wage of 1.20 yen, a family of 3 people can save 3.60 yen every day " also, “after 3 years, you can buy the land", were the beautiful empty promises written. For the salary at the time, it was extremely high, with word spreading that Brazil coffee was something like a tree that gives gold; making possible the dream of returning rich to Okinawa in a short period of time.

| Type of work | Coffee cultivation, harvesting, selection, drying etc |

|---|---|

| Term of the contract | About half a year (until the end of a coffee harvest) |

| Working hours | Enter into an agreement before the beginning of the work; according to Brazilian legislation and customs |

| Vacation | On Sundays, January 1st, November 3rd, and commemorative dates of Brazil |

| Wage | 1. In the case of daily: 2 thousand to 2 thousand five hundred réis (between one yen and twenty cents, and one yen and fifty cents) 2. In the case of a contractor: between 450 and 500,000 réis (30 cents yen) per bag of coffee |

| Residence | House of the same level as the European emigrants provided free of charge on the farms. Most are brick houses with a floor, without inconveniences with transportation and water. |

| Cost of travel | Round trip on behest the emigrant. However, part will be subsidized by the Government of the State of São Paulo. 40% of the subsidy must be reimbursed to the farm owners |

| Qualifications to emigrate | Over 12 and under 45. Family relationship centered around a couple with between 3 to 10 people |

Salary of 1910 as reference

| Daily | Monthly salary | |

|---|---|---|

| Farm day laborer | About .20 yen | About 5 yen |

| Carpenter | About .60 yen | About 15 yen |

| Primary school teacher | - - - | About 13 yen |

| Police Officer | - - - | About 14 yen |

| Brazil Emigrant's salary | Over 1.20 yen | Over 30 yen |

02. Emigration-related costs

A large amount of equity was needed to emigrate to Brazil. Despite the travel allowance offered by the state government of São Paulo, what was necessary in total was to get a little more than 150 yen per person and about 500 yen per family (3 people). Five hundred yen at the time was the amount that emigrants to Hawaii took back [to Okinawa] after working 3 years in a sugarcane plantation, saving and eating extremely badly. Therefore, those who were able to emigrate to Brazil had a certain income among people in the same village, above the middle class. Even so, most emigrants arranged the travel money either by selling or paying mortgage for their land by being indebted to the WĒKĪYĀ (rich), or by taking their part in advance in MUĒ (also known as TANOMOSHI, a mutual financing association). In other words, the emigrants were in debt and were in a situation which they were supposed to send money to Japan from the first day of their arrival.

Capital that the emigrant should prepare (per person)

| Travel cost help | About 20 yen |

|---|---|

| Cost of travel stamp | 1 yen |

| Travel mediation rate | 25 yen |

| Ship fare to the Port of Santos | 60 yen ※1 |

| Fees for quarantine, sterilization, vaccination etc. | 2.75 yen |

| Barge and luggage transportation fees | About .50 yen |

| Accommodation fee at the place of departure | About 3 yen |

| Money in hand | 20 yen |

| Ship fare from Naha to Kobe | 12 yen ※2 |

| Total | 144.25 yen |

CHUKUI KAZOKU

The requirements for emigrating were "over 12 years and under 45" and "family of more than 3 people and under 10 centered on a couple".

The emigrants, in order to return victorious soon, formed CHUKUI KAZOKU (arranged family) to raise money faster.

Young men, such as brothers, nephews, uncles and cousins joined a couple and the number of men and women was very disproportionate, and the percentage of children who were not a workforce was much lower. There were also cases of faking, declaring the own sister as wife, forming CHUKUI KAZOKU with complete strangers with no blood relation or even from different villages.

However, this was not a unique case from Okinawa, as it was also observed in KASATO-MARU emigrants from other prefectures such as Kagoshima.

In the interview, Kame OSHIRO attested that "there were family members I met for the first time at the port of Naha".

CHUKUI KAZOKU of Koki OSHIRO

| Name | Family relationship | Age (1908) |

|---|---|---|

| Koki OSHIRO | Head of the family | 19 years old |

| Kame OSHIRO | Wife | 17 years old |

| Choshin HOKAMA | Cousin | 25 years old |

| Kana OSHIRO | Cousin | 14 years old |

| Kamado OSHIRO | Wife’s cousin | 24 years old |

| Kame ARAKAKI | Nephew | 17 years old |

| Kosai GIBO | Uncle | 33 years old |

| Yasukichi OSHIRO | Wife’s uncle | 35 years old |

| Seikichi KANASHIRO | Wife's nephew | 15 years old |

| Seishi KANASHIRO | Wife’s uncle | 37 years old |

03. Reasons for Emigration

Reasons for emigration vary from person to person, with complex overlap of various elements. In the early 20th century, the Japanese government implemented an allotment program as part of the modernization policy, which destroyed Okinawa's unique system (shared ownership) and allowed individual land ownership. Therefore, laborers were no longer tied to the land, making it possible to get around anywhere else. Furthermore, selling their own land made it possible to arrange for large amounts of money to pay for the trip. The population of Okinawa Prefecture at the time had grown rapidly. The population of Okinawa Prefecture, which was 160,000 people in 1874, tripled to 480,000 people in 1903. There was little space and severe natural conditions such as typhoons, and with excessive taxes, rural communities had also weakened; failing to support the growing population and becoming a state of extreme poverty.

Under these conditions, emigration began to Hawaii in 1900, spreading throughout North America, Mexico, Philippines, Peru, and other regions thanks to the efforts of Kyuzo TOYAMA, the father of Okinawan emigration. Large sums were sent from those overseas and the returnees of emigration who were building new tile houses, starting new business with the capital they accumulated. They began to draw attention, blowing ever stronger the winds to throw themselves abroad; full of ambition.

Moreover, while being overseas the military service was suspended, thus there was among the young people of the wealthy classes, the desire to escape military service. Two cousins of Koki OSHIRO had died in the Japanese-Russian War. His parents and family, concerned about his strong physique, advised him to emigrate. Both Koki and Kame were from the most affluent families in the village. Thanks to their families, they managed to pay for the trip without debt, Kame said later in an interview.

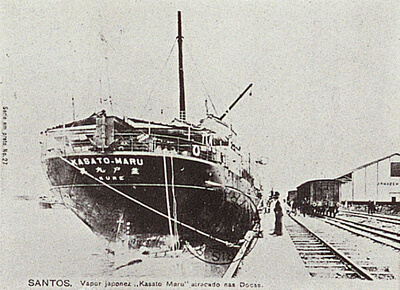

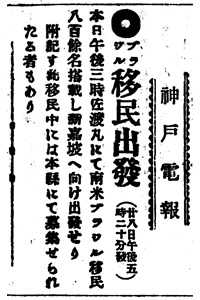

04. KASATO-MARU emigrants

In April 1908, 47 families totaling 325 people, boarded the regular ship KANAZAWA-MARU (from KAGOSHIMA YUSEN), traveling from the port of Naha to the port of Kobe, to arrive in time to leave for Brazil aboard the KASATO-MARU.

On the 28th day of the same month, the ship KASATO-MARU, with a total of 158 families, or the first 781 emigrants to Brazil, departed from the port of Kobe towards Santos (Brazil). The delay of 10 days occurred because KOKOKU SHOKUMIN KAISHA, the Imperial Colonization Company, failed to arrange the hundred-thousand-yen guarantee for the export permit of migrants to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The company temporarily kept the money that the emigrants had in hand, claiming that there was a risk of it being stolen on the ship, and part of that amount was allocated for that guarantee, then getting permission to leave.

05. The Sanshin and the Equator Festival

On the fourth day after departing from the port of Kobe, as KASATO-MARU approached the islands of Okinawa, the tide surged and they got caught in a downpour. In the midst of the rain that did not stop, the melody of sanshin sounded from the rooms of the Okinawan emigrants, who sang sad Okinawan songs, as though they were saying goodbye.

On the 27th day, they held the Equator Festival when they crossed the equator in the bay of the Malaysian peninsula. The interior of the ship was hectic in preparing the banquet and in the late afternoon, the emigrants were presenting the arts from their regions of origin. The troupe was animated with various numbers such as the brave and lively karate dance with the sound of sanshin, the dance of Satsuma, shamisen, Soma's song, shakuhachi, the recitation of poems and parade of costumes were agitated with hope for the future. That night, according to the records, when the sailor warned, "THE KASATO-MARU will cross the Equator now", all were tense and thus ended the party. The third-class rooms, in which KASATO-MARU emigrants spend about a month and a half, were large wooden rooms with several bunk beds lined up. The food on the ship was Japanese food of rice mixed with cereals, fish and preserved vegetables, with sporadically served fermented soybean syrup. The emigrants took the meal to their respective rooms there, in their beds or on the floor, to eat.

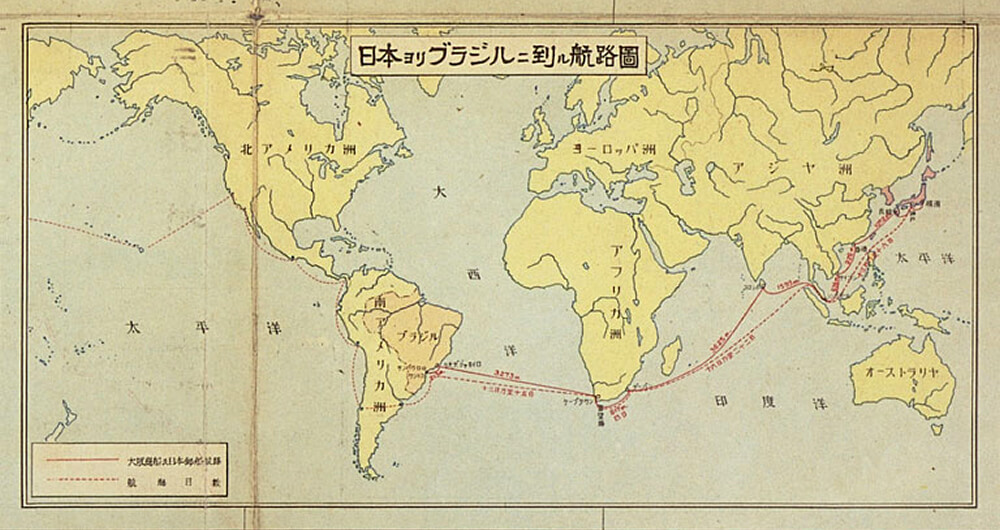

06. The Western Sea Route that Crosses the Atlantic Ocean

The KASATO-MARU proceeded without problems along the western route passing through the East China Sea, South China Sea, Indian Ocean, and Atlantic Ocean, traveling a full 11,700 nautical miles (12,668 kilometers). Stops were only made in the ports of Singapore and Cape Town for refueling, prohibiting passengers from disembarking fearing that they would become lost and not return to the ship.

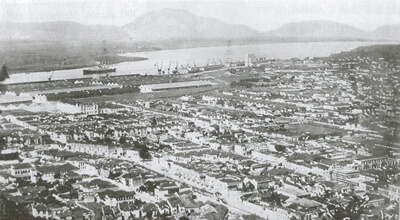

After sailing for 52 days, the KASATO-MARU arrived at the port of Santos (Brazil) on June 18, 1908. The magnificent mountains and a single white lighthouse first caught their attention after crossing the sea to the South American continent. A little after midnight finally came the image of the great port of Santos and people were excited by the fireworks that colored the night sky. The next morning, the sky was clear and the KASATO-MARU emigrants landed in Brazilian lands with a Brazilian flag in their hands.

The fireworks that KASATO-MARU emigrants saw that night were not to celebrate their arrival but instead from a Brazilian festival called, “Festa de São João”. The story of the emotion and seriousness with which Shinjiro SHIROMA gave the instructions to the people gathered on the deck is still told today. From adolescence to adulthood, SHIROMA devoted himself to the education of young people and this episode conveys how rigorous and honest he was, becoming one of the first pioneers of Okinawan emigration.

The fireworks that KASATO-MARU emigrants saw that night were not to celebrate their arrival but instead from a Brazilian festival called, “Festa de São João”. The story of the emotion and seriousness with which Shinjiro SHIROMA gave the instructions to the people gathered on the deck is still told today. From adolescence to adulthood, SHIROMA devoted himself to the education of young people and this episode conveys how rigorous and honest he was, becoming one of the first pioneers of Okinawan emigration.

07. Okinawan representative of KASATO-MARU emigrants

Shinjiro SHIROMA, a native of Nakagusuku-son, had embarked on KASATO-MARU as the representative of Okinawan emigrants. SHIROMA, who worked as a teacher and was a substitute director after graduating from the Okinawa Normal School, was allocated to the Floresta Farm, working as a rural worker, which he was not accustomed to. Later, he took part in the construction of the Northwest Railway, leading many Okinawans along the way, and in 1917, he ran a hotel in the city of São Paulo. SHIROMA has always provided guidance to Okinawan emigrants arriving in Brazil and gave an immeasurable effort in solving the numerous and difficult problems.

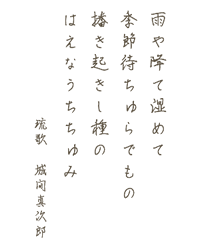

MACHI UCHISHI SANI NU/ HAENA UCHUMI/ (The planted seed, shall germinate) RYUKA (Poem of Ryukyu) By Shinjiro SHIROMA

※HAENAUCHUMI: I wont let not germinate, it will surely germinate It is said that he prophesied the emigration to Brazil with the tone of this expression

08. The First Emigrants from Okinawa to Brazil

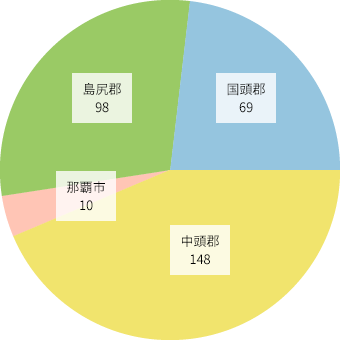

Looking at the statistical data of the first Japanese emigrants to Brazil, Okinawa prefecture has the majority with 42%, followed by Kagoshima and Kumamoto provinces. In Okinawa, regions such as Haebaru-son, Nakagusuku-son, and Misato-son sent more emigrants to Brazil.

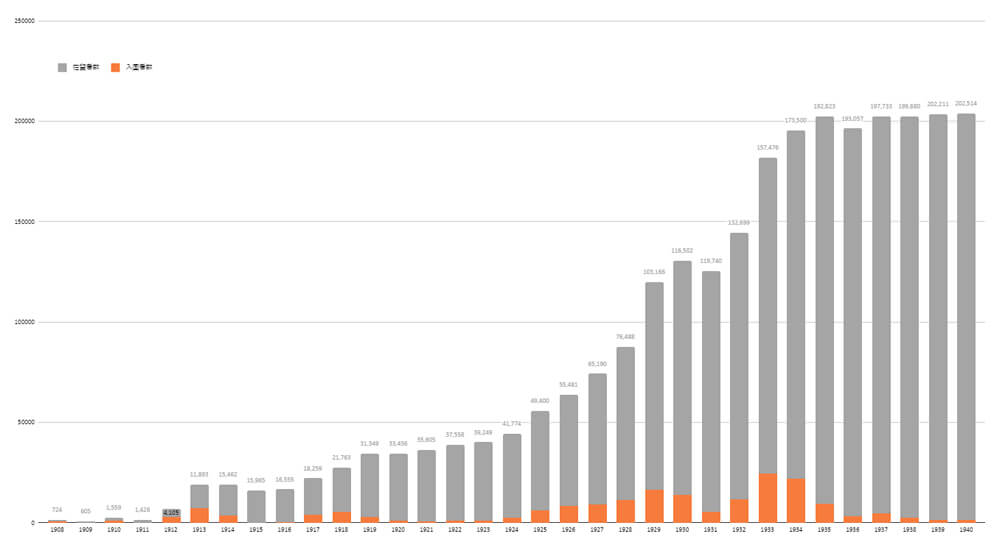

The reason that there are many emigrants from Okinawa Prefecture to Brazil is because the KOKOKU SHOKUMIN KAISHA (Imperial Colonization Company) concentrated on seeking emigrants in this province and due to the 1908 Gentlemen's Agreement between Japan and the United States, which limited new emigration to Hawaii and the continental U.S. region. Kame OSHIRO, the KASATO-MARU emigrant, said she initially intended to go to Hawaii, not Brazil. From that year of the first emigration to Brazil until 1940, there were two restrictions for Okinawans to travel and a total of 187,186 Japanese emigrants entered Brazil. About 200,000 Japanese resided in Brazil in 1940, with Okinawan emigrants reaching 16,287 people

Place of origin of the first Okinawan emigrants to Brazil - Number of emigrants by municipality, number of families and by gender

| Municipalities | Family members | Men | Women | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gun (District) | In 1908 | Nowadays | ||||

| Kunigami-gun | Hanedi-son | Nago-city | 1 | 9 | 1 | 10 |

| Nakijin-son | Nakijin-son | 2 | 12 | 2 | 14 | |

| Motobu-son | Motobu-cho | 2 | 14 | 2 | 16 | |

| Nago-city | Nago-city | 2 | 15 | 2 | 17 | |

| Kushi-son | Nago-city | 1 | 5 | 1 | 6 | |

| Kunigami-son | Kunigami-son | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | |

| Iheya-son | Iheya-son | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | |

| Oogimi-son | Oogimi-son | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | |

| Nakagami-gun | Misato-son | Okinawa-city | 8 | 28 | 7 | 35 |

| Katsuren-son | Uruma-city | 1 | 5 | 1 | 6 | |

| Chatan-son | Chatan-cho | 2 | 5 | 2 | 7 | |

| Nakagusuku-son | Nakagusuku-son | 7 | 33 | 7 | 40 | |

| Nishihara-son | Nishihara-cho | 6 | 22 | 7 | 29 | |

| Yomitan-son | Yomitan-son | 0 | 12 | 0 | 12 | |

| Ginowan-son | Ginowan-city | 0 | 8 | 0 | 8 | |

| Gushikawa-son | Uruma-city | 0 | 11 | 0 | 11 | |

| Naha-city | Naha-city | Naha-city | 1 | 9 | 1 | 10 |

| Shimajiri-gun | Mawashi-son | Naha-shi | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| Tomigusuku-son | Tomigusuku-city | 3 | 20 | 4 | 24 | |

| Tamagusuku-son | Nanjo-city | 1 | 3 | 1 | 4 | |

| Oozato-son | Nanjo-city | 1 | 16 | 1 | 17 | |

| Gushikawa-son | Kumejima-cho | 1 | 4 | 1 | 5 | |

| Haebaru-son | Haebaru-cho | 7 | 37 | 8 | 45 | |

| 47 | 276 | 49 | 325 | |||

First emigration from Japan by prefecture of origin Emigrants to Brazil by gender (1908)

| By Prefecture | Men | Women | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Okinawa | 276 | 49 | 325 |

| Kagoshima | 127 | 45 | 172 |

| Kumamoto | 51 | 27 | 78 |

| Fukushima | 53 | 24 | 77 |

| Hiroshima | 32 | 10 | 42 |

| Yamaguchi | 18 | 12 | 30 |

| Ehime | 14 | 7 | 21 |

| Kochi | 14 | - - - | 14 |

| Miyagi | 7 | 3 | 10 |

| Niigata | 6 | 3 | 9 |

| Tokyo | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| Total | 600 | 181 | 781 |

Okinawan Emigrants in Brazil

Okinawan Emigrants in Brazil

The Okinawa Prefecture sent the first 325 emigrants to Brazil in 1908. Then, with a 3-year interruption, the second group of 421 people went to Brazil in 1912, but the Japanese government prohibited emigration for 4 years due to the scarce numbers of farm workers. Eventually, 2,138 people are sent in 1917 and 2,204 people in 1918, but with new a ban for 7 years. Giving new start to travel in 1926 but limited to some conditions, finally in 1936, all travel restrictions are lifted.

09. The House of Immigrants of São Paulo and the farms

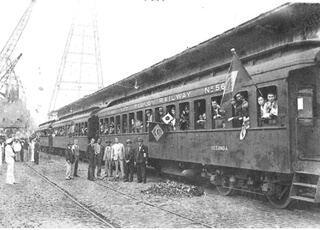

The KASATO-MARU emigrants who landed on the pier of Warehouse 14 in the Port of Santos, went by train to the House of immigrants of São Paulo. There they made preparations to go the farms, being inspected by customs and for preparatory shopping. In the local newspapers, there were articles evaluating Japanese immigrants very well by organization, hygiene of clothes, and by their robust body despite having a short stature. From June 26 to July 6, KASATO-MARU emigrants were allocated as settlers with interpreters on 6 large farms: Canaã, Floresta, São Martinho, Guatapará, Dumont, and Sobrado. The farms were divided by region of origin. Those who went to The Canaan Farm were only Okinawans from the Nakagami region (central region of the island) and to the Forest Farm only Okinawans from Shimajiri (southern region of the island) and Kunigami (northern region of the island).

10. Life and poverty at Floresta Farm

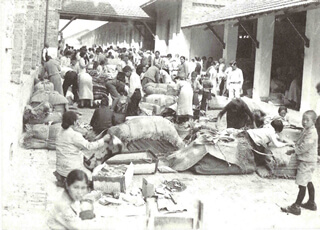

The emigrants who arrived at the farm dedicated themselves to the coffee plantation, working without rest, from sunrise to sunset. Early in the morning, men and women used stairs, scraping the coffee fruits off from the branches with their own hands and dropping them into a large cloth where the fruits were gathered. Then they removed the leaves and dirt by shaking high in the sieves. The fruit harvested after being measured and bagged was carried in the wheelbarrow or cart to the drying area.

The emigrants received treatment similar to that of slaves by the farm owner and supervisors. Obedience to the rules with vigilance, sometimes through violence and forced submission to farm owners. To buy utensils of daily need there was no other choice but to buy from the Venda (store) for exorbitant prices, connected directly to the farm owner thus being no way to save money despite hard work.

The no refund of emigrants' money issue was also greatly influenced. The Imperial Colonization Company gathered money from the emigrants, including Okinawans, as something temporary, but the money was not returned either in the House of immigrants or on the farms, further squeezing their lives.

As the coffee tree took about 3 years to bear fruit, the scarce harvest due to bad weather and the floods of the river brought great insecurity to the lives of the emigrants.

As the coffee tree took about 3 years to bear fruit, the scarce harvest due to bad weather and the floods of the river brought great insecurity to the lives of the emigrants.

11. A Paradise on Hearsay, A Hell at Sight

The actual amount of coffee harvested on the farm was a quarter of that announced by the Imperial Colonization Company, and the emigrants who believed in the history of the "gold-giving tree" were betrayed. It was said that one person made 5 to 6 bags a day and a family (of 3 people) took 135 yen per month, but in reality, a family made 1.5 bags a day and only took about 34 yen per month.

Many of them ended up in debt to get the money for the trip, needing to return the money as soon as possible so as not to cause problems to their parents, siblings and relatives.

- Source: BURAJIRU OKINAWA KENJIN IMINSHI KASATO-MARU KARA 90 NEN (Okinawan Immigration to Brazil - 90 years since KASATO-MARU)

- Source: BURAJIRU OKINAWA KENJIN IMINSHI KASATO-MARU KARA 90 NEN (Okinawan Immigration to Brazil - 90 years since KASATO-MARU)

- Source: BURAJIRU OKINAWA KENJIN IMINSHI KASATO-MARU KARA 90 NEN (Okinawan Immigration to Brazil - 90 years since KASATO-MARU)

- Source: BURAJIRU OKINAWA KENJIN IMINSHI KASATO-MARU KARA 90 NEN (Okinawan Immigration to Brazil - 90 years since KASATO-MARU)

12. Escaping Farms and Wandering

In order to send money as soon as possible to their homeland, where people helped them to get the money for the trip, without waiting for the term of the contract (half a year or a year) they fled the farms, moving to Santos, where they could work as longshoremen, with a higher income. There were 6 families, 31 people, of the KASATO-MARU emigrants who first fled the Canaã Farm, the first Okinawans to settle in Santos. The longshoremen were called dock workers, dedicating themselves to carrying coffee bags of 60kg, being an important workforce that supported the Brazilian trade

The reason that KASATO-MARU emigrants joined one after another in Santos may be because they got higher income work information from those who fled before and thought about the possibility of returning to Okinawa one day. For them, Santos was the closest place to their home Okinawa in the distant land of Brazil.

Then, looking for better work, more than half of the Okinawan emigrants from KASATO-MARU moved to Argentina. However, jobs of good conditions were few and many emigrated again to Brazil; constantly moving

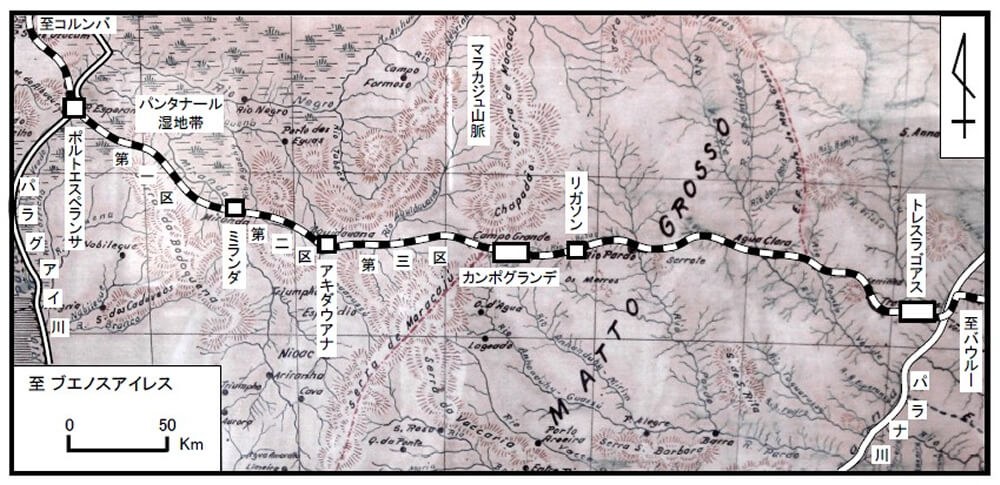

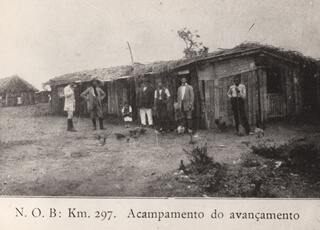

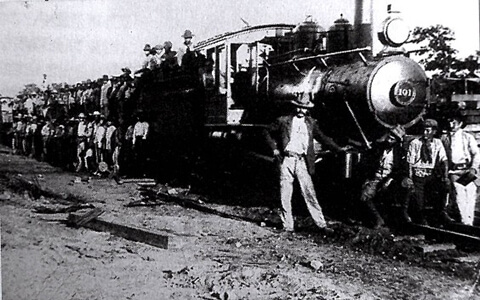

13. The Noroeste Railway that Paved the Way for Life

One of the things that paved the way for the lives of the emigrants who were constantly migrating was the work on the Noroeste railway that connected Porto Esperança (west) to Três Lagoas (east) of the State of Mato Grosso. Railroad workers, compared to the workers of coffee farms, received a much higher pay of 5,000 réis (equivalent to 3.06 yen.)

The construction work of the railway (about 450 km long) that began in 1908 was perceived as a competition to see who would arrive first in Campo Grande that was in the middle of the east and west ends. The railroad that connects Brazil to Bolivia crossing the continent was a major project that would open a new continental transport route. The inauguration of the Noroeste railroad, which was called a Brazilian national policy, was held grandly in Porto Esperança, the starting point on the western side.

The Okinawan emigrants of KASATO-MARU who took part in the construction of the northwest railway were about 75 people, with 40 more people joining them. They were Okinawans and other Japanese from Kagoshima prefecture and other Japanese who migrated from Peru. It is said that more than 100 Japanese emigrants took part in the railroad construction.

14. The Workers of the Noroeste Railway

The measurement of the area of the rails, picada (clearing the forest), earthmoving, installation of the (railroad) ties, laying of the rails, fixing the ties and rails, filling with earth in the ties, and flattening the ground are the stages of the construction of the railway. The ties brought by the trains were loaded in pairs and aligned on the path of the line 1 meter away from each dormant.

The railroad construction workers had a very hard job. Building the railroad sometimes involved suffering attacks from mosquito swarms, clearing the native forest where ferocious wildlife and poisonous snakes hide, filling land in swampy areas to the point of being submerged in waist-deep water; the difficulties of the work were endless.

The railroad workers could not receive adequate treatment even when they became ill because they lived in constant motion with the camp advancing according to the construction. For this reason, about twenty KASATO-MARU emigrants died from malaria. Many wives took part in the construction and because of the heavy work environment, there were sad cases of women losing their babies.

Collection of PROJETO MUSEU FERROVIARIO REGIONAL DE BAURU (Bauru Regional Railway Museum Project

Collection of PROJETO MUSEU FERROVIARIO REGIONAL DE BAURU (Bauru Regional Railway Museum Project

15. The Uchinanchus Who Participated in the Construction of the Noroeste Railway

Many Okinawan emigrants participated in the construction of the Noroeste railway. The 73 KASATO-MARU emigrants (originally from Okinawa and Kagoshima) led by Koki OSHIRO who left the farm, descended the Atlantic Ocean to the south, passing through Buenos Aires, and up the Paraguay River to Porto Esperança, the western base. Migrants arriving from the distant Peru, crossing the Andes Mountains, also came from Buenos Aires using the same route. In Três Lagoas, the eastern base, Shinjiro SHIROMA and 45 Okinawan emigrants joined.

-

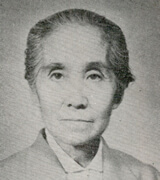

OSHIRO Kame

Tomigusuku-son★ -

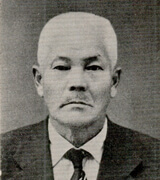

OSHIRO Koki

Tomigusuku-son★ -

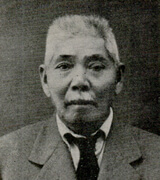

![OSHIRO KANA [Eikichi]](image/chapter2/sec3_peple_03.jpg)

OSHIRO KANA [Eikichi]

Tomigusuku-son★ -

OSHIRO Kamado

Tomigusuku-son★ -

OSHIRO Uto

Tomigusuku-son★ -

OSHIRO Ryoso

Tomigusuku-son★ -

HOKAMA Kame

Tomigusuku-son★ -

HOKAMA Mito

Tomigusuku-son★ -

ARAKAKI Bisaburo

Haebaru-son★ -

ARAKAKI Kame

Haebaru-son★ -

YOZA Keisaburo

Haebaru-son★ -

SHIROMA Tetsuo

Haebaru-son★ -

SHIROMA Saichiro

Haebaru-son★ -

HIGA Tyutyoku

Ozato-son★ -

CHINEN Goro

Ozato-son★ -

TERUYA Kama

Ozato-son★ -

![SHIMABUKURO Kama [Nabe]](image/chapter2/sec3_peple_17.jpg)

SHIMABUKURO Kama [Nabe]

Misato-son★ -

CHINEN Matsu

Misato-son★ -

HIGA Tokumatsu

Nakagusuku-son★ -

HIGA Ushi

Nakagusuku-son★ -

MIYAHIRA Matsu

Chatan-son★ -

IKEHARA Jiro

Yomitan-son★ -

TABA Ushi

Nishihara-son★ -

KOHAGURA Gen

Ginowan-son★ -

ZAHA Seiken

Motobu-son★ -

NAKAHODO Sengoro

Motobu-son★ -

YONAMINE Jingoro

Nakijin-son★ -

![ARAKAKI [TAMASATO] Muta](image/chapter2/sec3_peple_28.jpg)

ARAKAKI [TAMASATO] Muta

Haebaru-son★ -

AKAMINE Kame

Tomigusuku-son■ -

YAMASHIRO Kosho

Kyan-son◆ -

MIYAHIRA Itiei

Haneji-son◆ -

NAKAO Gonsiro

Haneji-son◆ -

GUENKA Yokichi

Haneji-son◆※ -

SHIROMA Kasuke

Kunigami-son◆ -

Source: ZAIHAKU OKINAWA KENJIN GOJUNEN NO AYUMI (History of 50 years of Okinawans in Brazil), Terra de Esperança Kibo no Daitsi (The hope's land), BURAJIRU NIHON IMIN 100NEN NO KISEKI (The 100-year trajectory of Japanese emigrants in Brazil), MIRAI HE TSUGU EISON (The descendants that connects to the future), 325 Okinawanos do Kasato Maru (supplement of SHASHIN DE MIRU BURAJIRU OKINAWA KENJIN NO REKISHI: 1 século de História em Fotos (A Century of history in photos) ★=KASATO-MARU (1st group of emigrants) ■=KANAGAWA-MARU (3rd group of emigrants) ◆= Migration from Peru ★※Collection of Sonoko AKAMINE ◆※Collection of descendants of Yokichi GUENKA

16. The Completion of the Noroeste Railway

The construction of the Noroeste Railway that began in 1908 by the west and east finally had the East-West interconnection completed about 30 km west of the city of Campo Grande on August 31, 1914, on its 7th year.

The last place where the rail bar was placed was called Ligação (Connection) Station and the steam locomotive that was affectionately called, "Maria Fumaça" began operating.

In the vicinity of Campo Grande, due to the many fertile and cheap lands, there were people, who with the capital accumulated with the construction of the railroad, rented/ bought the land and began agriculture. Among the railroad workers who were forced to move as the railroad expanded, those who found a way out to establish themselves, developed the land by joining forces and built a colony.

Of the colonies developed by Okinawan emigrants in the vicinity of Campo Grande, there were Mata do Segredo, Bandeira, Imbirussu, Mata do Ceroula, and Rincão among others. There were people who worked on many jobs like Koki OSHIRO did, in areas related to the railway (head of workers, train driver, construction contractor, joinery, etc.). There were those who settled in the urban center, who dedicated themselves to trade and laundry, seeking new possibilities in agriculture and commerce, different from the livestock industry, thus rapidly developing Campo Grande.

Source: SHASHIN DE MIRU BURAJIRU OKINAWA KENJIN NO REKISHI: 1 s?culo de História em Fotos (A Century of history in photos) Below) Logo of the Noroeste Railway of Brazil @EstradadeFerroNoroestedoBrasil

Source: SHASHIN DE MIRU BURAJIRU OKINAWA KENJIN NO REKISHI: 1 s?culo de História em Fotos (A Century of history in photos) Below) Logo of the Noroeste Railway of Brazil @EstradadeFerroNoroestedoBrasil

Estrada de Ferro Noroeste do Brasil

Noroeste Brazil Railroad, Noroeste means northwest, and its main line left Corumbá station from the border with Bolivia to the inner part of the State of São Paulo at Bauru station. Bauru Station was developed as one of the main railway junctions in the country. Part of the railway was discontinued, but the locomotive Maria Fumaça can be seen in the form of a tourist train.

17. The Japanese Colony and the Terra Roxa

The reddish soil conducive to coffee cultivation is called "Terra Roxa" in Brazil. Roxa indicates the purple color, and when the soil gets wet with rain, the red becomes more intense and shines.

The completion of the Noroeste Railway changed the times, rapidly developing the train line vicinity, from a time when people and supplies were mainly transported by boat.

From the 1920s, the land along the Noroeste railway was sold by lots and many Okinawan emigrants settled as coffee or cotton farmers by renting or on their own lands.

In 1933, there were many Okinawans living in the regions of the Lins station (164 families), Promissão station (155 families), Bauru station (52 families), Cafelândia station (47 families) among others. Especially in the Lins station region, 71 families of Okinawan emigrants gathered in the Aliança district of the Uetsuka Colony no. 2, becoming one of the largest Okinawan communities to influence Okinawan artistic activities in Brazil.

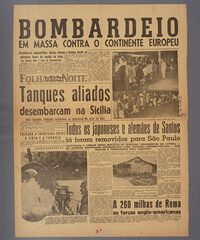

18. World War II and Emigrants to Brazil (pre and post-war)

With the outbreak of World War II, Japanese emigrants in Brazil, as well as in the US and Peru, suffered as citizens of an enemy nation. However, compared to other countries, most were a part of the “The Victorious” (KACHIGUMI), those who did not doubt the Japanese victory even after the Japanese surrendered, and there were cases of bloodshed on the "The Defeated” (MAKEGUMI) Japanese and frauds, creating a great mess.

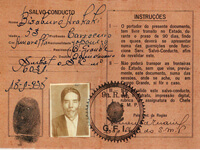

Freedom Limitation of the Enemy Nation Citizens

As the world advanced into war, the environment surrounding Japanese emigrants became increasingly difficult. In 1939, carrying a foreigner registration and an identity document becomes mandatory. In August 1941, the publication of newspapers in Japanese language was prohibited and for emigrants who could not read Portuguese, and access to information also became very limited. In addition, the Brazilian government issued an order to control the citizens of the Axis countries (Japan, Italy and Germany), prohibiting the distribution of texts in their respective languages, talking in public places in their mother languages, discussing the world situation, meetings in private residences, and even restricting the freedom of movement. In March 1942, the assets of the citizens of the Axis countries were frozen.

Confinement and Forced Evacuation

With the beginning of the war between Japan and the U.S., several rumors and malicious propaganda spread; only worsening the impression that the Brazilians had in relation to the Japanese. The Brazilians reacted violently and there were incidents such as attacks and raids on the Japanese merchants throughout the country. In Campo Grande, Koki and Kame OSHIRO's store was set on fire, losing all possessions in a single night.

And the Japanese residents in the Japanese neighborhood of the city of São Paulo and the city of Santos were compelled to evacuate. On July 8, 1943, citizens of Axis countries that lived within a radius of 50 km from the coast of São Paulo were forcibly evicted in less than 24 hours. The Japanese who were forced to evacuate did not have time to dispose of their property, thus losing their homes, and were then temporarily gathered in the House of Immigrants of the State of São Paulo, then forced to move to the inland of São Paulo. At the time, the Consulate of Japan in Santos had been closed and the situation was such that there was no one to protect them. Among them, there were pregnant women and young children. The city of Santos was where Okinawans were concentrated, with more than 3,500 people, or 450 families, who were forcibly evicted. In Brazil there were no cases of being taken to U.S. concentration camps as in Peru, but Okinawan emigrants suffered major material damage.

19. The Post-War Chaos of the Japanese Community

KACHIGUMI

On August 14, 1945, it was possible to hear the transmission of Japan accepting the terms of the Potsdam Declaration, but for many Japanese emigrants it did not reach them with accuracy. Shindō Renmei, a secret society of fanatical nationalists, replaced Japan's "unconditional surrender" with "unconditional surrender of the United Nations," spreading that Japanese defeat was a rumor and that it was actually Japan's victory. This discourse spread quickly among the Japanese and was embraced by many people who refused to accept the defeat. Those people were called KACHIGUMI, or the victory faction (The Victorious), those who believed in Japan's victory, and it is said that about 90% of Okinawans supported the KACHIGUMI. However, people who believed in the Japanese victory were not just in Brazil, but also among Japanese residents in Hawaii, Peru, and other regions, in addition to Japanese soldiers and officers detained abroad as prisoners of war.

MAKEGUMI

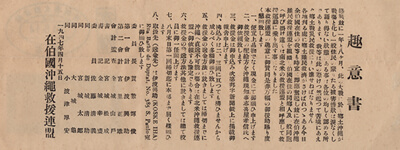

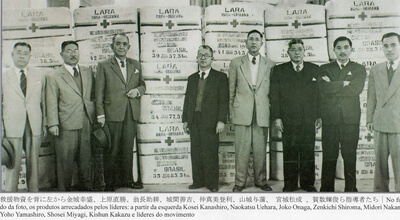

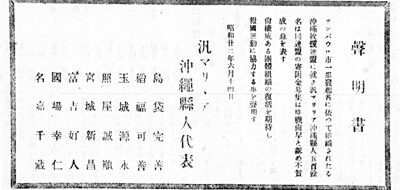

The KACHIGUMI were the vast majority in the Okinawan communities of Brazil and attacked the people who recognized the defeat (MAKEGUMI) nominally, isolating and expelling them from the communities. Despite this, there were people who knew how to accurately understand the new times instead of succumbing, tried to help Okinawa (their homeland), which was reduced to ashes in the Ground Battle. Volunteers such as Josei ONAGA, Naokatsu UEHARA, and Midori NAKAMA created the ZAIHAKU OKINAWA KYUEN RENMEI (Okinawa Relief Union in Brazil), later renamed the Brazilian Committee Aid to Victims of War in Okinawa, and published their prospectus in the newspaper in April 1947. The Okinawa Relief Union published the group's report monthly, reporting about the campaign to raise funds and about the situation in Okinawa, then sent to Okinawan communities making a call for them to help with the campaign. And Sukenari ONAGA, who were publishing a Japanese-language newspaper before the war, published SHUSENGO NO OKINAWA JIJO (Okinawa situation after the war) by himself, informing Okinawans in Brazil. It is said the funds and supply raised were sent to Okinawa as LARA Supply, or the Licensed Agency for Relief in Asia (LARA). However, the KACHIGUMI did not cooperate and published advertisements against the aid movement.

Offered by the National Diet Library of Japan